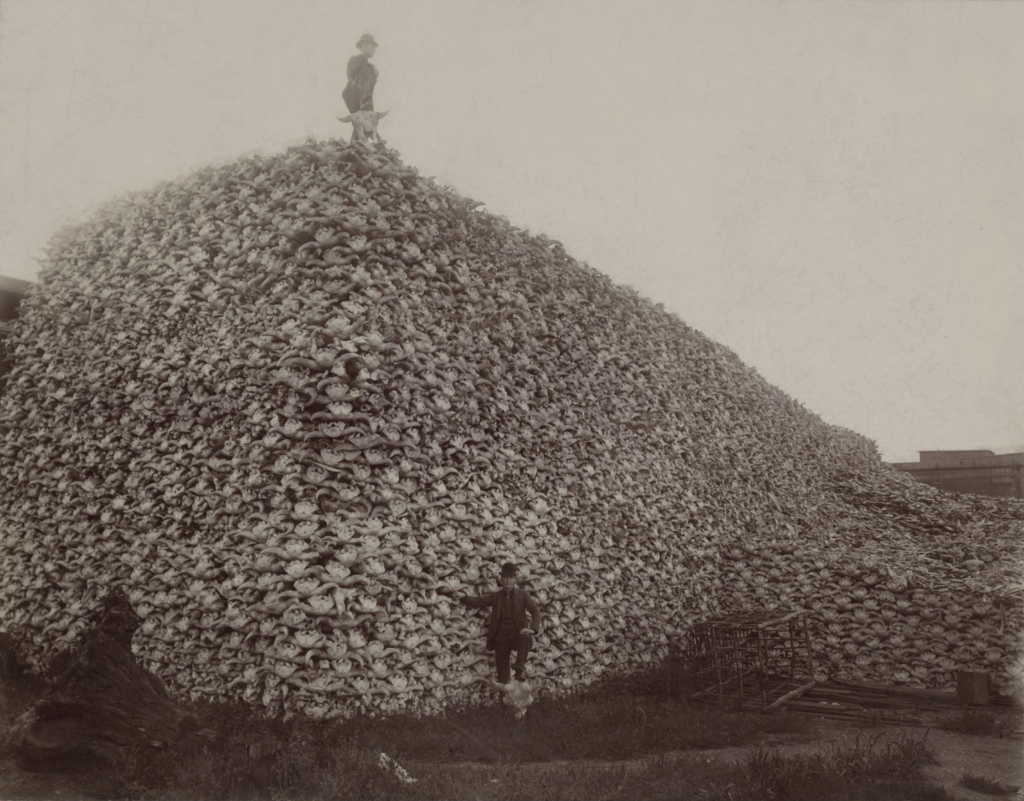

We recently created an event at North Wind Aikikai designed to introduce a bit of fun and creativity before the cold prevents us from being outside. We invited dojo members to share a picture of their “spirit animal”. What you see pictured above was my choice for the event. After considering many options, I settled on the bison, also known as the buffalo. I have been spending time this spring, summer and fall roaming some of the lands that the bison once roamed. My time in this wilderness has stimulated my curiosity about the ecosystem. I have been asking myself “what was this land before”, “what has this land become under our human influence” and “what is this land seeking to be”. To understand the land however it seemed important that I understand the animals that once thrived upon it. This curiosity has made the bison my spirit animal this year.

The meaning of “Spirit Animal”

Honestly, I have no idea what having a “spirit animal” means. I know my spirit has often been inspired by the natural world however. I also know that I am increasingly curious about, humbled by, and grateful for the various residents of the farm (and greater) ecosystem I have been studying. The beaver that damned up “two thumb creek” have told me a lot about themselves for instance. The local deer that I have taken over the years through hunting have encouraged me to study more about where they live, their hardships, what the eat during a drought, and how they seek to communicate to each other. Fox, raccoons and hawks; buzzards, loons, and leapord spotted ground squirrels; red winged black birds, salamanders and pocket gophers are some of the countless characters of the land. Each of these characters is telling me a story and I am trying to learn how to listen. I’m not certain but I think each of these stories is my story too. These stories are our story in fact. It is an ancient story and a story of our future simultaneously. I have chosen the bison as my spirit animal, because I imagine that I am being asked to tell the bison story. I don’t imagine I am worthy to the task either as a listener or writer, but my spirit is stirred to try nonetheless.

Bison Herds on Every Prairie

The bison was an instrumental part of the North American landscape. One night I found myself asking, “How many bison where there before the arrival of the European colonists?” The map below amazed me. The red line shows where the bison once were.

Conservationist William Temple Hornaday took on the arduous task of answering the question “how many bison were there” during the 1870’s with this map. Its estimated that there were between 30 and 60 million bison roaming the majority of the continent before the arrival of colonizers. However, by the year 1900, the population numbered only 300. The reason for this near extinction of the bison is simple, tragic, and still unresolved.

The bison were the lifeblood for many of the indigenous people of North America. However President Ulysses S. Grant saw the destruction of buffalo as a solution to the country’s “Indian Problem.” A concerted, government sanctioned and government funded effort was made to eliminate the bison in order to simultaneously eliminate the native people of the continent. President Grant assigned two generals to this task, William Tecumseh Sherman and Phillip Sheridan. In October 1868, Sheridan wrote to Sherman that their best hope to control the Native Americans was to “make them poor by the destruction of their stock, and then settle them on the lands allotted to them.” In 1867 two treaty’s were signed that temporarily ended the “Indians Wars”. It was during this period that the enlisted men still stationed in the Great Plains began to decimate the herds of bison in earnest. Seargent Bill Cody, later known as Buffalo Bill claimed to have killed 4,280 buffalo during this period. “One colonel, four years earlier, had told a wealthy hunter who felt a shiver of guilt after he shot 30 bulls in one trip: ‘Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.'”

The American Settlement Surge

America was born upon some fundamental ideas. One of these was known as “manifest destiny”. This was the idea that the United States had a divine calling, as determined by God, to expand its control across the North American continent spreading its values and gaining access to its abundant resources.

Another fundamental idea in the origins of our country is the concept of dominion. Most translations of the Bible use the word “dominion” repeatedly. In the book of Genesis it is written:

“Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth.” Genesis 1:28

My wife, a professor of religion, has explained to me that that amongst biblical scholars, the translation of the original Hebrew term used in the Bible to “dominion” has been controversial. I am certain that an important lecture, or course, or career could be made exploring this topic. For the time being, I simply want to identify that at the time the bison were being eradicated from these lands, the guiding principle for that effort was that the wilderness and the indigenous people who had been living upon it for thousands of years should be dominated or killed in fulfillment of God’s will.

Keystone Species

Today, ecologists refer to certain animals as “keystone species”. This term is used when the benefits that animal provides allow for the thriving of many other species within that same ecosystem. What makes them “key” however is that without their presence, the whole ecosystem itself is threatened. I originally became interested in learning more about this when I began to consider providing habitat for pollinators on the farm. That interest set off a chain of events that have lead to my appreciation of the bison as an essential spirit in the pantheon of plants, insects and animals that resided upon the Great Plains.

A bison eats around 24lbs of food a day. All of that food is dry vegetation and a bison will forage for 9-11 hours a day in order to meet those dietary needs. This foraging however has been the engine of the prairie ecosystem as it evolved over thousands of years. In fact the earliest ancestors of the American bison we know of today existed over 1 million years ago. Our most recent archeological evidence suggest that the earliest humans were in the Americas was around 22,000 years ago. This means that the bison were evolving with these lands, these plants, insects, and animals for around 98% of their existence before the arrival of any humans. It was only in the last fraction of a percent of their existence that the bison faced the threat of extinction with the arrival of Columbus.

As bison roamed the prairies they served to stimulate an ecosystem. By chewing on the vegetation they stimulated more growth from the plants. Most native grasses have evolved to grow more vibrantly after a grazing ruminant like the bison passes by. Moreover, while the bison’s body is turning that vegetation into vital energy (vital enough to escape predators at speeds of 35 miles an hour) their massive body is also leaving waste behind. Bison saliva, urine and dropping are rich in nutrients making excellent fertilizer and creating habitat for a host of birds, bats, insects, microbes, fungi and more. Additionally, as the bison hoofs and massive bodies moved about the prairie they churned the earth, aerating the soil and oxygenating plants root system. Through rolling in in the mud they created wallows that would hold water and create a small micro-ecosystem in the prairie for other animals, insects and birds.

One of the farm practices I have studied and started exploring is the use of cover crops in combination with livestock rotation. The concept is inspired by the natural process of prairie management that the bison were a part of. The beauty of this system is that it is mutually beneficial. The plants, livestock, soil and farmers all benefit. In fact, the added benefit of carbon sequestration through the maintenance of living soil may be the solution to droughts like we saw this year, severe flooding, overuse of fertilizers, and the desertification of soil that is expanding through climate change. The film Kiss the Ground on Netflix offers us some hope towards that end.

Indigenous Peoples Day or Columbus Day

I worked to publish something today because I believe that the story of the bison is simultaneously the story of our indigenous American ancestors. I have been reading the work of Robin Wall Kimmerer. Her book Braiding Sweetgrass has been something of a guidebook for me as I try to “hear” the story of the land around me. More importantly her work carries the wisdom of a people who lived for so long upon these lands as to learn the essential value of mutual interdependence that the land whispers over centuries of living together. We must willingly make room for these stories and this wisdom. While we may have the technology for remarkable control of our planet, we do not yet have the wisdom necessary for managing that control. Scholars like Toby Orb argue that this lack of humility and wisdom may be the weakness that leads to the end of humanity. I believe that the voices of our native people, people like Mrs. Kimmerer serve is an access point to that wisdom.

Dominion or Stewardship

My days on the farm this summer included regular walks on our land and the public lands surrounding our land. Sometimes I was looking for deer; antler sheds, droppings, beds, and vegetation they’ve been eating. Giulio is very interested in bow hunting deer now. He has his eyes on the big bucks. I am just trying to be worthy enough as a hunter. Taking life is always humbling for me.

On my hikes, I have been trying to learn the plants around me. I have been using an app called “seek”. Although I have observed that smart phones can create as much frustration for me as pleasure, I do appreciate a technology that can speed my journey towards knowing the land. Simply showing the phone’s camera a plant, insect or animal, the app can identify it for me. The process is successful about 50% of the time but its allowed me to discover which of the plants in these woods and prairies are native and which are introduced, or invasive. I also carry a “hatchet hoe” (as I call it) on my farm hikes. I use that to whack at a buckthorn, or a thistle or any plants that I have been taught are invasive.

One of my teachers is a human. A kind woman who works for the Xerces Society. This is a non-profit organization dedicated to restoring native pollinator habitat. She made a long trip this summer to see what my land offered. This specialist is familiar with the land’s pollinator plants and pollinator insects as they were before the attempted eradication of the native people through the killing of the bison. From her, I have learned a couple important things. First, I don’t know a great deal more than I do know. Second, the land has a story. And third, the land needs stewards. Colonization has brought with it destructive forces that undermine the natural balance that had been established over centuries. Buckthorn (a very aggressive invasive shrub) is one example. Its clear from my walks that I could spend a lifetime removing the buckthorn. I just may.

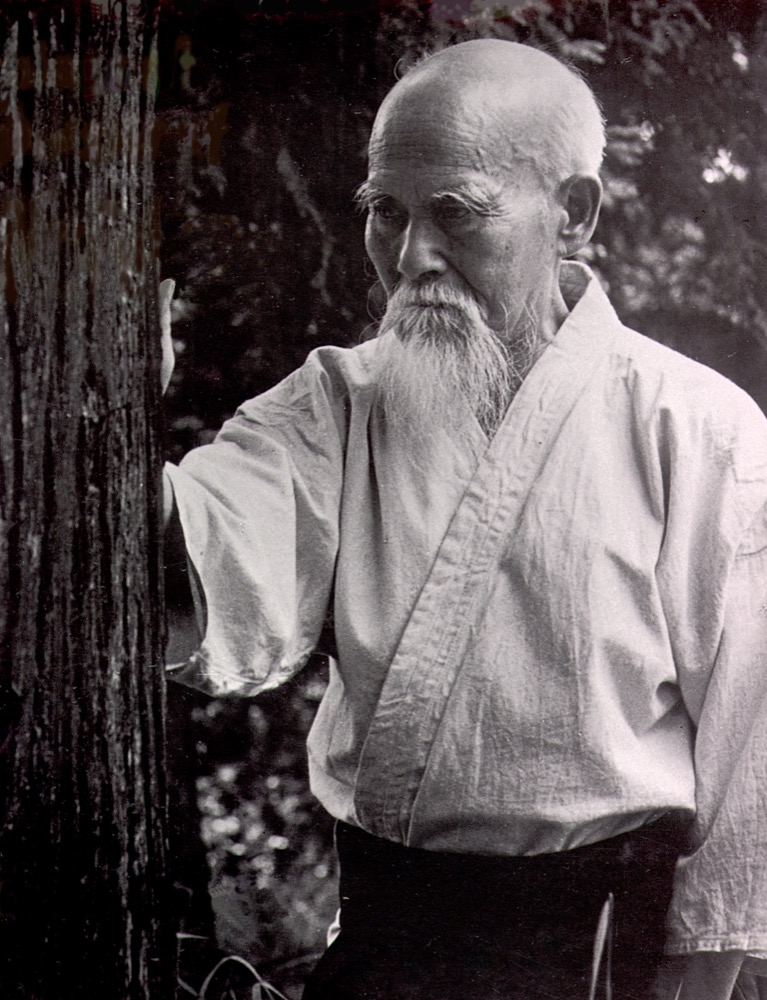

“Aikido is medicine for a sick world” ~O’Sensei

I feel an obligation to contemplate this message from O’Sensei frequently. It may be why I pursued a medical vocation after my years in an Aikido apprenticeship. We are currently in the midst of a “mass extinction event” comparable to only five other such events in the 4.5 billion year history of our planet. The difference however is that this event has not been brought on by a giant asteroid impact or a global ice age. We are the creators of this event. My search for the spirit of the bison is inspired by the need to understand the sickness at the heart of this. O’Sensei explained that “we have forgotten that all things emanate from one source”. The bison spirit is our spirit. All the animals our aikido students have chosen are our spirit. Listening may be the first medicine we need.